Hail the Dark Lioness - The queer gaze of Zanele Muholi

Remember me when I'm gone

For I

Wrote stories for the nation to read

Stood without fear and told my story

(…)

I show my rapist how strong I was

regardless that he poisoned my blood with his HIV

(…)

I had a message to deliver and a vision to see

I tried

(…)

SO… REMEMBER ME WHEN I'M GONE!

FOR…without a doubt

I'm with peace with my maker and creator

The poem Remember me when I'm gone, written by the queer activist, and poet Busy Sigasa who died from HIV in South Africa in her 25 is exhibited with Sigasa's portrait in Zanele Muholi's retrospective in Tate Modern giving the spirit of the whole show. An extraordinary show that guides us through South Africa's queer communities talks about discrimination and exclusion, hate crimes and trauma, the construction of the colonised female subject and the struggles for its deconstruction by contemporary activism, LGBTQ communities and women solidarity.

The non-binary photographer Zanele Muholi is one of the most dynamic figures in queer activism today, fighting over women and LGBTQ' rights in the difficult post-colonial conditions of South Africa.

Born in 1972 in Umlazi, South Africa, they settled in Johannesburg to study graphic design at the age of 19. In 2002, after co-founded the Forum for the Empowerment of Women (FEW), they joined the Market Photo Workshop in Newtown, the art school founded by the famous photographer David Goldblatt. They had their first solo exhibition at the Johannesburg Art Gallery in 2004, and in 2009 they obtained their MFA in documentary media from the Ryerson University of Toronto. Since then, they have won numerous awards, while their work has been exhibited worldwide in numerous institutions and international art shows, including Documenta 13, the 55th Venice Biennale and the 29th São Paulo Biennale.

Growing up during the Apartheid regime (that officially ended in 1990) and still living in Johannesburg, Muholi uses the photographic medium to criticise the post-colonial condition. Their work reveals colonial's origin racist stereotypes and how they have influenced the formation of local identities and the resulting discrimination and hate policies that still prevail in their country. At the same time, photography is their means of claiming visibility and voice for marginalised groups. Driving force of Muholi's vigorous activism is a deep desire to make us see through art, hitherto indistinguishable and socially silenced communities.

Their big retrospective at Tate Modern is an in-depth acquaintance with their work, both in the creative and activist part. One of the most interesting radical and innovative elements of Muholi's work, is the relationship of these two actions, the fact that the areas of activist and artistic activity interact, co-shape and evolve at the same time, constantly feedback each other. In fact, Muholi denies their characterisation as artist preferring that of a visual activist. With this vision, in 2006 they founded the Inkanyiso collective, a media platform that "produces, educates and diffuses information in many commonalities, especially those that are marginalised and falsified by the mainstream media". Inkanyiso is an empowerment tool for the local queer communities. It offers information about queer life, rights, struggles and activity, about art, creativity and entertainment as well as political awareness.

In the uneven socio-political landscape of post-colonial South Africa, where, although the first African country to legalise same-sex marriage, LGTBQ people still encounter extreme conditions of exclusion and hate, Muholi's art activism offers a real shelter to the marginalised and traumatised.

The Tate tour thus, as it introduces us to the main lines of their activist and artistic course, apart from a retrospective, offers a dynamic knowledge of the South African queer community. We watch the events of its members, parades and demonstrations, the savage attacks they receive and funerals of gendered violence and hate victims, ceremonies and weddings, the eccentricities and the inevitable stylistic and behavioural appropriations from the heteronormative culture; but also, their dreams, aspirations and personal stories, all depicted through interviews, hundreds of portraits and scenes of everyday life, intimacy and endless struggles.

What is extraordinary about these photographs is that they are not presented as views of another universe. On the contrary, they glorify the naturalness of human condition's diversity, both in the differences and the similarities among individuals of all sexes.

Sometimes they are harsh and wildly grounded as in their early and sensational series Only half the picture, that focuses on hate crimes' survivors. Muholi's gaze here follows the traces of pain and fear of violated bodies. Their protagonist is the traumatised female body.

They are often tender and bright as in the Being series that tracks queer couples' daily lives, inspiring pure erotism, warm intimacy, and euphoria.

In series such as the Queering Public Spaces and Brave Beauties, the feeling is glorious and assertive. Here the queer subject claims and occupies the public space, surpassing the heteronormalised rules of beauty.

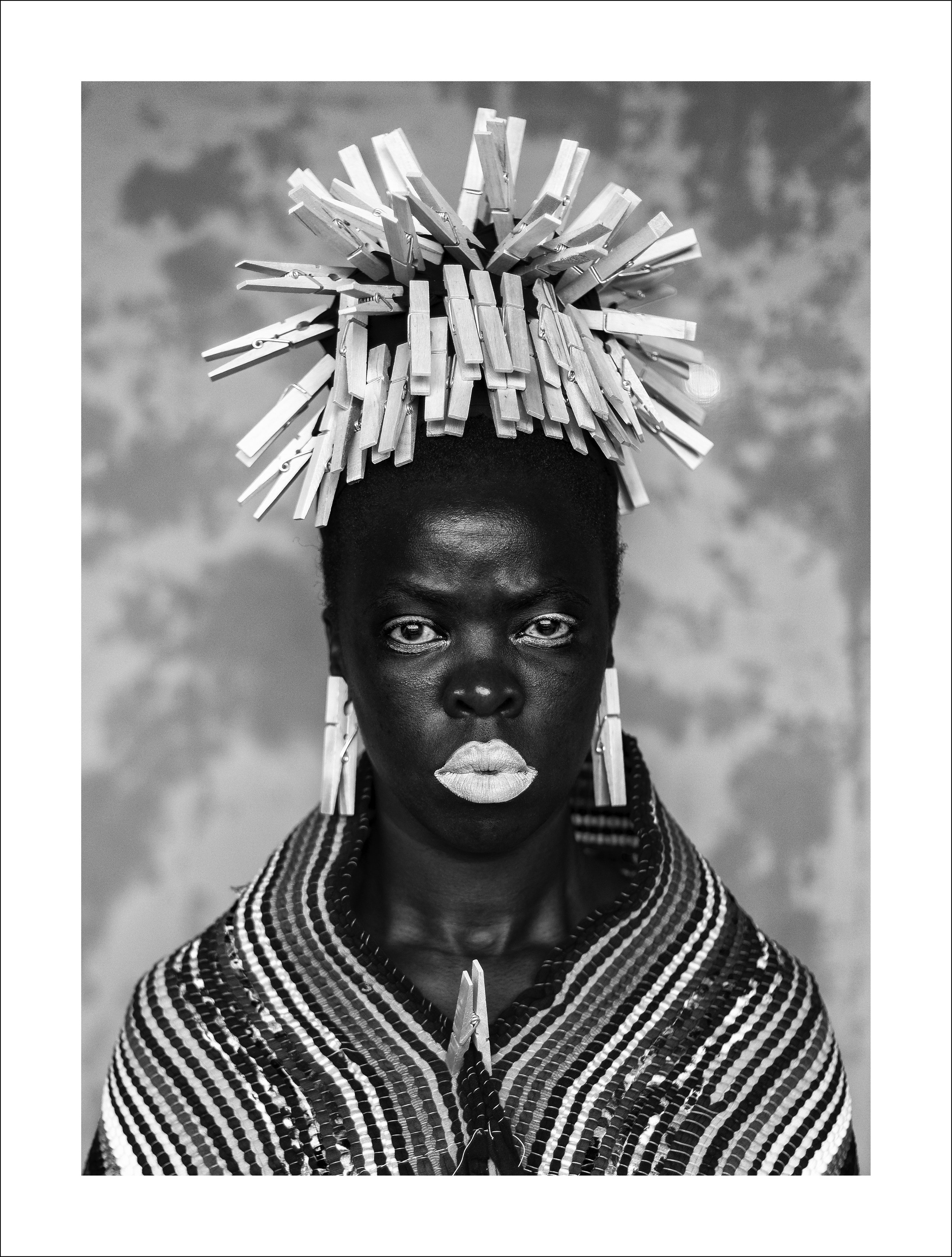

In the charming and mysterious project Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail the Dark Lioness in the Zulu language), Muholi is self-photographed by reproducing with careful sophistication stereotypes and obsessions concerning the exotified post-colonial black subject and the socially imposed performances of femininity. Here, it is the subject's gaze that prevails. The queer gaze becomes the voice of the voiceless. Eyes can say what cannot be said, even the hardest and roughest truths. That is why, in this exceptional series, Muholi's eyes, keeping an uncompromised intensity, seem to follow their spectator everywhere.

In all their manifestations, Muholi's photographs have an admirable balance between the information they attempt to convey and the chain connotations arising behind the sensitive use of aesthetic codes.

The wonderful and powerful series of portraits Faces and Phases, perhaps most of all in the borderline between archive and art project, is a work on progress that started in 2006 and continues until now. It captures members of the local queer community as they grow and evolve. The empty places between the frames are a dramatic reminder that some have been tragically lost through all those years, emphasising that their struggle is still on.

In the last hall of the show, all these numerous, beautiful faces in various phases of their lives, cover the walls with their presence or absence, looking at us courageously, with eyes that radiate self-awareness and confidence, claiming the equal visibility they deserve.

London 2021