Review - Bruce Nauman at Tate Modern

If John Cage is the respectful grandfather of Conceptual art as it progressed from the mid-20th century up to now, Bruce Nauman is its funny uncle. The uncle who pranks, paints genitals on the hangman game, performs pathetically unsuccessful magic tricks and hides cunningly behind the wall not to see him while filming us.

The uncle who becomes rather disturbing in order to destabilize us.

From the very beginning of his career, Nauman treated artistic practice as a field of absolute freedom, an unlimited space beyond any conventions of material, form or content.

He graduates from the University of California in the late 60s, one of the most exciting periods of the 20th century, in a chaotic and hippie America, vibrating by the revolts against the Vietnam War and the fervent struggles for human rights, while the Cold War climate was favoring state surveillance. At the same time, in the art fields, the glorious emergence of cryptic Minimalism - Judd has already published his Specific Objects – is counterbalanced by the new-born need for a harsh reality expressed by the Happenings movement - inspired and supported by Fluxus and Arte Povera in Europe. As a young artist, Nauman listens to, absorbs, and adopts all these promiscuous elements on his own terms.

His inspiration sources are significant and diverse: Lucy Lippard talks about art dematerialization, Joseph Beuys practices the everyday as art, and Vito Acconci and Carolee Schneemann make body art. In the West Bank, John Cage calls for a turn towards randomness and silence while the East Bank, Robert Smithson plays with entropy and natural extinction ideas.

Nauman's big retrospective show in Tate Modern comes up timelier than ever, not only because of the welcoming video in which he washes his hands with obsessive meticulousness, but mainly because it implies confinement issues by emphasizing the game between absence, claustrophobia and monitoring as echoes of all his influences.

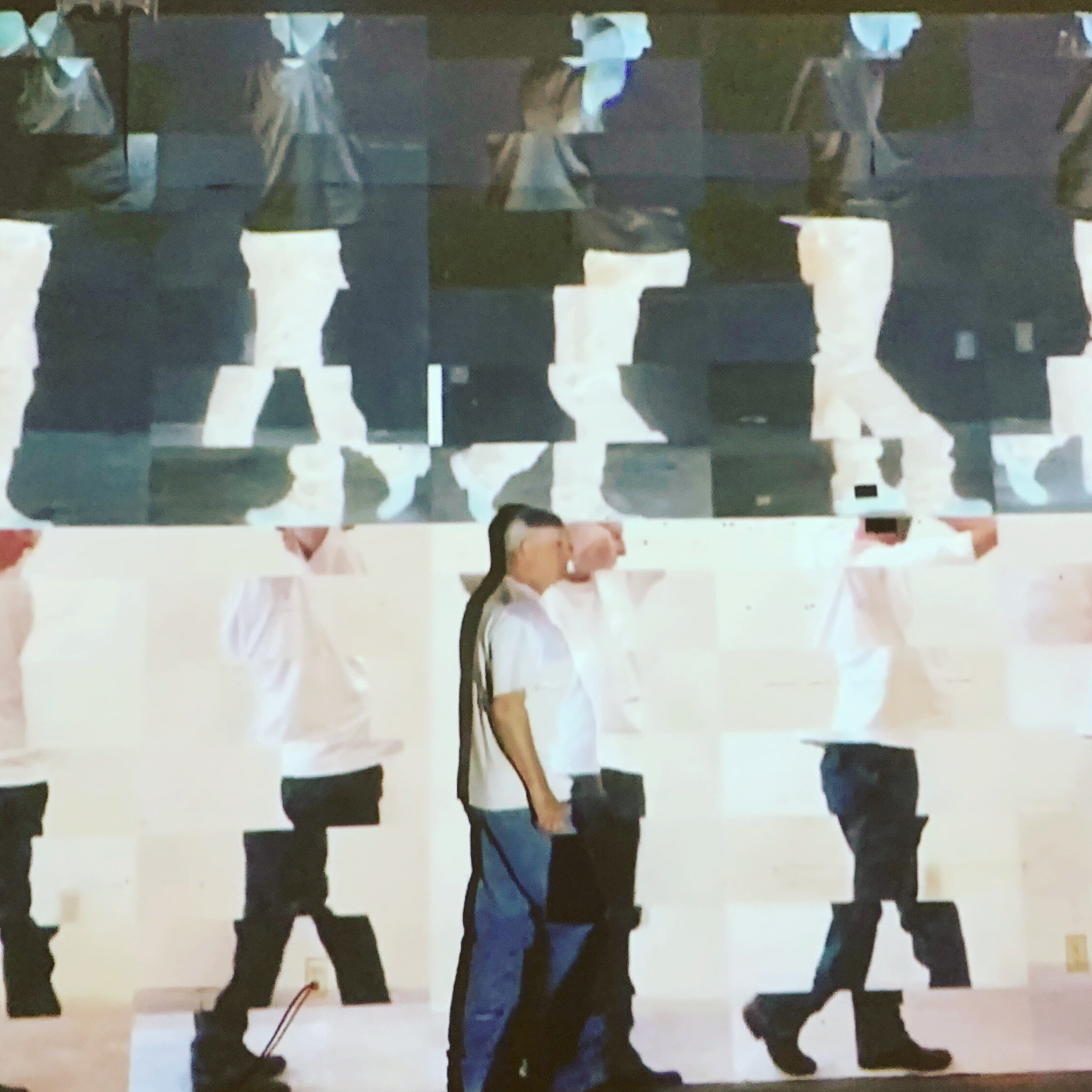

The presentation of this game begins in the first half of the exhibition with the multi-channel night "watching" of his studio, a project in whose title the (playful) reference to Cage (Mapping the Studio. Fat Chance John Cage, 2001) as a signifier of creative randomness is anything but random.

The survey continues to a review of his first studio works, where creative anxiety flirts with the outrageous, the pointless and the boredom while intersecting with his early artistic research on the points of contact between performance and sculpture – the emblematic "contrapposto", the painful successive bounces on the wall and the comic "face-yoga" before ending with ruthless immediacy in his iconic and even scary 1974 cage. That being after some moments of claustrophobic awkwardness among angry clowns.

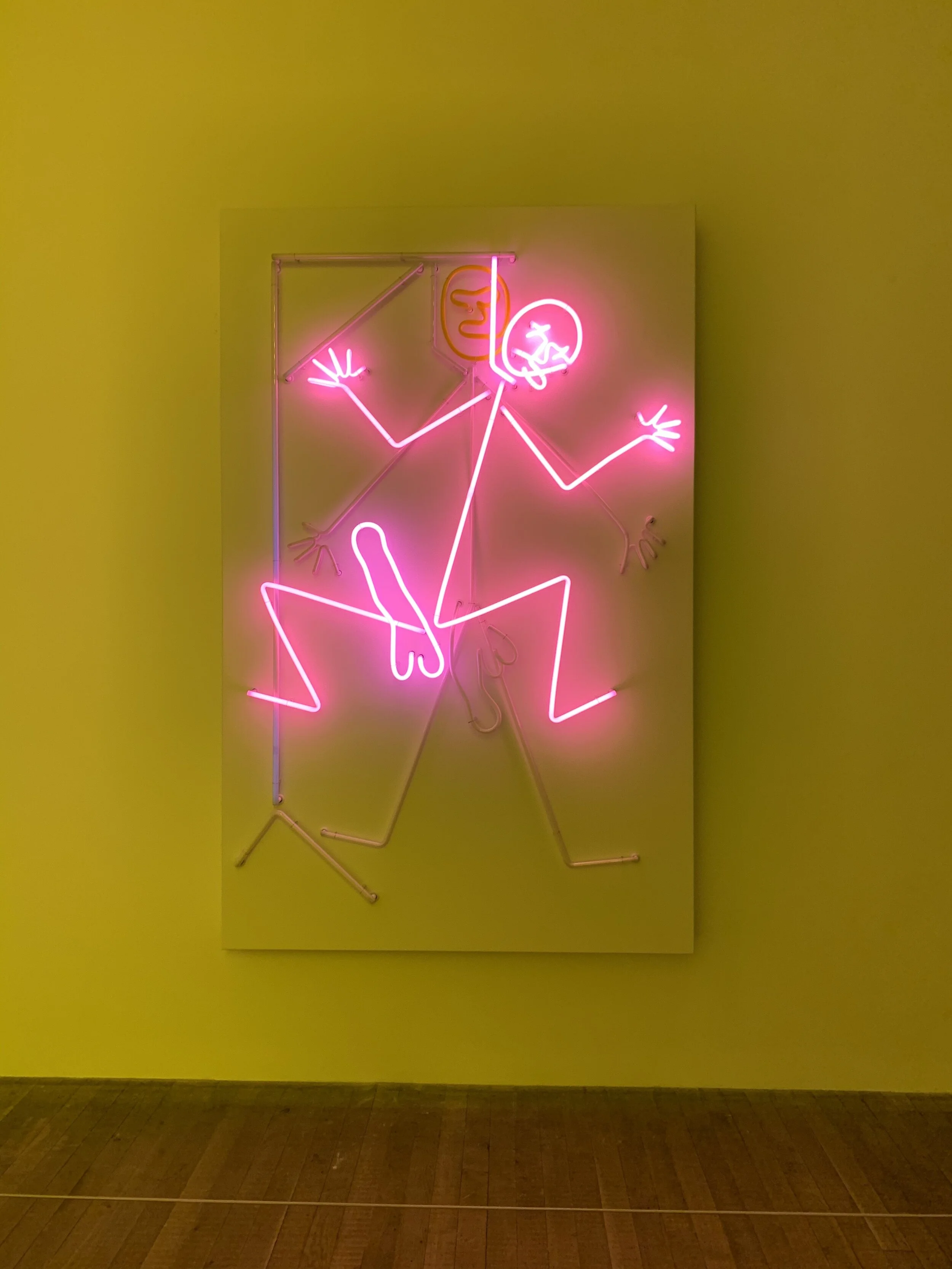

What is the real artist, after all? A depressed clown doomed to futile gestures or a guinea pig? These seem to be the actual questions that Nauman poses through his work, and which he has answered in advance – with subversive sarcasm – in the neon sign of the entrance: The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (1967).

These mystic truths are to unfold in the second half of the exhibition, hidden behind children's toys (the socking Hangman and the musical/electric chairs), magic tricks-odes to failure, and the dark concrete poetry of his multiple neon inscriptions.

In the meantime, an almost imperceptible sense of swing is everywhere. Words fluctuate in different contexts or repeat in different intonations; the void acquires a concrete cube's weight as space under a chair; the lightness of a clown is counterweighed by the severity of his paranoia.

Maybe the only thing anyone could accuse Nauman of is cynicism. Watching and listening retrospectively to his work, you feel that the ultimate secret truth is the absence of a way out of the human existence's senselessness. However, if the artist's highest purpose is its revelation, then the least attempt of its disguise becomes a secret act of compassion (Know and die/Sleep and live).