No woman no cry

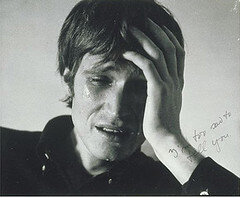

Bas Jan Ader, I am too sad to tell you

2 or 3 years ago, when we were still visiting art sites and exhibitions, I had been to Tate Modern, in Tania Bruguera show in Turbine Hall, about empathy and solidarity. Apart from the main installation in the centre that had to do with the human body temperature and how a lot of people together can achieve something impossible (or the struggle for the impossible and the notion of a mass movement), there was also a crying room. Literally, a room that invited you to cry and “helped” you to do so through a kind of natural “tears’ enhancer”, a substance similar to the one onions give out. In fact, it was a room calling for the awkward act of public crying.

Yesterday in an all-women online course a young, bright and independent woman asked us to excuse her if she may cry as she was in her days. And it was then that it really stroke me: why she had to ask for an excuse? Why crying in front of others is such a big deal (when at least it is not a funeral case). Why we have to ask for an excuse for manifesting some momentary feeling, some emotion or even a crack? What is so damning about that? About feeling?

Trying to answer, in a clumsy and awkward way, I have to dig into my own reaction toward crying, my crying and the others’.

I had always been feeling like my desire for crying was a weak spot, a manifestation of my inadequacy, of not deserving any respect and confidence. The fact that I couldn’t stop my tears when I was feeling like crying (that might have been caused by a sudden thought, an emotional film, a song or the feeling of injustice and sometimes anger) made me unbelievably shameful. In short, I hated my self for first wanting to and then not be able to prevail crying. Being so, I have asked a hundred times for an excuse for crying and even now I feel ashamed of crying even in front of my loved ones. And I still have to stop myself all the times from telling my son not to cry.

Laughing is another way of showing strong emotion but it would never be a reason to ask for an excuse. Everybody can laugh at any time with any company, outdoors or indoors, loudly or low and nobody would be critical. No one would ask for an excuse about laughing a little more than usual because she had some good news today or just because. And definitely, no one would ever tell to a boy not to laugh, that boys don’t laugh.

But crying is a different thing. It reveals a weakness.

Of course, it is not easy to deal with a crying subject. Public display of sorrow is something that can create a heavy atmosphere, an embarrassment, even a guiltiness and “destroy” a conversation. Keeping our feeling to ourselves is a sign of politeness of civilized manners. However, if people were looser about crying, politeness would find a way to deal with it. Nobody could cry forever as no one is laughing forever. Confronting any manifestation of sorrow disappointment and emotion as something usual, frequent and natural would be liberating. After all, everyone feels better after some crying when needed, while restraining it can create more stress. If crying was not considered as a sign of breakage nobody would be discomfort before it.

Looking at works of art that picture crying, as anyone would expect, most of the times they depict women or children. Crying in culture (past or contemporary) is an action that you would never expect from a man. Big boys don’t cry. Crying is for girls. For years and years, generations to generations, boys have been growing up with these catchphrases. No place for weakness to a man behaviour, no permission for crying.

The stereotype of the crying woman is a primary picture of weakness (I am constantly thinking of Roy Lichtenstein’s Crying Girl), while the woman that can hide her tears is the strong, the admirable one.

All in all, as crying is an action attributed mostly in children and women —the fundamental weak subjects, the Others than the strong male ones— that means that is shameful.

The behavioural canon that rules our everyday life, the unwritten laws and social protocols are all prescribed through binary principles. Good and bad, strong and weak, hard and soft, tall and short, high and low, masculine and feminine. Having identified feminine with the negative pole everything characterized as female becomes a weakness. Whatever makes a man seem like a woman is laughable, whatever makes a woman seem like a man is admirable.

There are scientific acts reporting that women, having more shallow tear ducts, meaning that they are more quickly full and more easily spilt over, are more prone to cry. Meanwhile, other scientific researches prove that testosterone could restrain crying. Finally, certain hormones of the woman body, like prolactin, are strongly connected with powerful emotions and crying.

Women may cry more because of their physiology (patriarchy is blamable for the rest). And as that physiology deduced crying to a woman-thing, automatically it becomes shameful. It is not like if a crying subject is incapable, weak or untrustful. You can be rational, capable and excellent in anything you do and still crying. It is that a crying subject is confronted as womanish and whatever womanish can not be effective in the patriarchal prism.

In “I am too sad to tell you”, Bas Jan Ader is crying in front of the screen. He is crying and crying and nobody knows why, he seems desperate and inappropriately vulnerable, especially for a man. Watching him crying and mourning for such a long time produces discomfort and uneasiness. A vulnerable man, a man who cries publicly for such a long time, who doesn’t hide his despair, who actually records his despair is a spectacle that unsettles and annoys as it crashes with a basic social contract. The one that forms the fundamental masculinity and dictates a woman’s inferiority. Patriarchy is a matter of forces, the weaker looses. Patriarchy needs strong, not crying men and vulnerable weeping women and prescribes masculinity and femininity likewise.

But Bas Jan Ader is not afraid to show vulnerability, to sabotage thus the male protocol. He confronts head-on the stereotype and invites us to contemplate the taboo of crying in public.

Just like Tania Bruguera calls us to cry altogether about everything inhuman patriarchal regimes have created, crying without shame. Cause crying is not shameful, patriarchy is.